- Home

- G L Rockey

Truths of the Heart Page 2

Truths of the Heart Read online

Page 2

“Sorry. What are you doing?”

“Brushing up on player stats, then going over to the Niner stadium with Cork for the game. What time is it there?”

She looked at her Timex: “Three.”

“Noon here.”

Rachelle said, “Nervous?”

“Bout what?”

“The game.”

“Nah, piece a cake, playing for keeps.”

She knew better. “How do you think the Lions will do?”

“The Lions suck this year.”

“How's the weather in little cable-car land?”

“Huh?”

“Tony Bennett….”

“Christ, that fag.”

“How's it otherwise?”

“Rain, fog, cold, my nose is plugged up ever since we landed and my arm is killing me, back too.”

“Sorry.”

With a touch of sarcasm, he added, “How's the weather in beautiful Lansing?”

“Beautiful.”

“You're going to listen to the game aren't you?”

“Where is that again?”

“Babe, where have you been? Lansing it'll be on WLSC-AM.”

“Oh, good, I'll listen.”

“And don't forget, flight gets in tomorrow afternoon, 5:30, meet me at the baggage claim, curb side.”

“Please.”

“And I'll want to get something to eat, then hit the rack. Don't forget to paint your toe nails, know what I mean?”

“Hope you're not too tired.”

“Never. All ready for next weekend?”

“I'm psyching myself up.”

Pause, “What's that mean?”

“Nothing, be good, have a wonderful game and a safe flight, see you tomorrow.”

Pause, “Did you forget something?”

“Like what?”

“I love you.”

“I love you too.”

“Love you babe, bye.”

CHAPTER TWO

His crew cut hair the color of seasoned leather, Carl Bostich's receding hairline belied his age—twenty-seven. Just over six feet one, he weighed two hundred and fifteen pounds. His swamp-water green eyes looked at you like he knew the answer before you asked the question. Sports announcers often noted that his hands “look like a bunch of ripe bananas.”

Carl and Corky, passengers in a clunking Checker Cab, the San Francisco stadium ten minutes away, Carl ignoring the no smoking sign and placing a Kool King cigarette between his thin lips. He lit up with a Bic throwaway lighter. The cab driver, knowing his passenger's celebrity, said nothing.

Carl had taken up smoking to calm a “why-me” obsession that had its origin in a fluke accident. Media headlines, etched in his memory like a ghoulish joke, said it all:

CARL BOSTICH INJURED, MAY NEVER PLAY AGAIN

BOSTICH OUT FOR GOOD

LIONS LOSE STAR QUARTERBACK

So too etched, were the press reports:

Heisman Trophy winner, playing-for-keeps Carl Bostich, the super star college quarterback who broke all Notre Dame team passing records, destined by many for the NFL Hall of Fame, is kaput. In his third year with the Detroit Lions, in the blink of a tackle, super bowl dreams, Hall of Fame, earnings potential, were all snuffed out courtesy of a crushing tackle by Chicago Bear's linebacker “Crazy Dog” Kurt Tucker.

Raw Thanksgiving Day was a mocked promise for Carl Bostich … Thursday November 28, minute left in the first half, Ford Field, light wind out of the south, Chicago 10, Detroit 10, Carl Bostich back to pass was dropped like a sack of potatoes … out of nowhere, a blinding jolt knocked Bostich in the air … Bostich’s throwing arm looked like a broken sausage … Docs say Bostich’s elbow crushed … Star quarterback will never throw the pigskin or any ball for that matter, with velocity again … Bostich, in lieu of a signing-bonus, opted for hefty up-front ticket sales percentages, performance dineros, sees millions of green backs flushed down el toilette-o … Most tragic, Bostich’s famous ego is left without a preening platform.

So Carl, determined to stay close to football (since peewee league he had ate, slept, and breathed the game), was about to try his luck at a career in broadcasting. He would be working with radio veteran “Voice of the Lions,” Corky Dixon. Corky was also Sports Director of Detroit's WJJ-AM—the flagship station of THAX Broadcasting's radio empire. Carl would be doing color. Corky, as always, play by play. If this worked out, Carl had his eye on TV and the network 'big-guys'.

A compulsive self-preener, Carl still had a classic steroid gulping V-shaped body. Because of his upper body chest size, his suits, shirts, sports coats were tailor crafted. His shoes were also custom made to cushy his 13-E foot size. Coupled with winning smiles and bear hugs, Carl toppled the opposite sex like a ten-pin-bowling ace. His trademark expression “playing for keeps”, he bragged to former team mates that he, in one year, had been in the pants of “a thousand broads”.

Carl especially liked trophies. He had won many in his years of football stardom. Shelves and walls, wherever he happened to be “shacking up”, dripped with his awards. In a way he thought of Rachelle as a trophy. But to his thinking this golden beauty was soft to the touch, most alluring, a breathing bed-warmer. And she touched back!

Carl dragged his Kool and shot a remark to Corky: “Well Cork, if this game turns out as predicted, maybe the Niners will send in the cheerleader squad.”

“If they do, I'm going in as tackle.”

Carl laughed nervously as he, once again, recalled the smashing tackle that crippled his throwing arm.

CHAPTER THREE

After her jog, Rachelle returned to her Bessey Hall office, tidied up her desk, and walked to the faculty parking lot where she coaxed her lime-green Saab sedan to life. She had bought the car show room new, paid it off in three years, become emotionally attached.

Pulling out of the parking lot, she felt a bit of nostalgia. She turned and drove west to Grand Ledge. In fifteen minutes, turning on Tulip Street, she slowed and stopped in front of a white bungalow that had been her childhood home. She noted that the house was in need of a paint job. And the maple in front had grown so very high. She remembered her father mowing the lawn.

On the drive back to her house on Lake Lansing, hungry, she stopped to grab some 'rabbit food' at a Wendy's salad bar. At a window table, eating, her cell phone rang. She looked at caller ID—Carl. She answered, “Hi.”

Carl: “Hey babe, where you at?”

“Just grabbing a bite to eat.”

“Where?”

“Wendy's.”

“I hate them joints.”

“Where are you?”

“Forty-niner’s stadium.”

“That must be exciting.”

“Playing for keeps, babe. Don't forget to catch the game, it'll be on

WLSC-AM radio in Lansing. Kickoff six here, that's nine there.”

“Oh, okay.”

“Don't forget to pick me up tomorrow, get in at 5:30.”

“Got it.”

“Love you.”

“Me too.”

Finished with her salad, Rachelle drove, northeast of the M.S.U. campus, to her home which overlooked quaint Lake Lansing. The house, at 5900 East Lake Drive, was a two-story custom designed chalet constructed of cedar logs. The lower street level was a two-car garage. The property, on an end lot twenty feet back from the water’s edge, was beside two acres of wooded township-owned land. On a quiet bay with vista views of the lake, the distant tree-lined shore was mirrored picture perfect in the quiet water. An occasional deer or heron wandered in the back yard. At night, breezes wafted across the lake rippling the water at the shoreline.

The house Rachelle's, Carl had been living here since March. After many weeks of frustrating rehabilitation at a Detroit clinic, Carl had gained use of his right arm but, like the team doctor had said, his throwing velocity was gone, so was his accuracy. Marriage to Rachelle never a question in his mind, he had proposed before the injury. Wanting to live in Det

roit, he goaded Rachelle to quit teaching, sell the house. For Rachelle that was an out-of-the-question, not-on-the-table option, period. She loved her house, East Lansing, M.S.U., her colleagues; it was home. She knew, too, a little nugget from the tragic death of her father, that once something precious is gone, it is gone forever.

Not-on-the-table-options settled, Carl moved to 5900 East Lake Drive, Lake Lansing. But in May, when the Lions hired him to team up with Corky on the radio broadcasts, Carl's three-time-a-day lament became, “I told you we should have moved to Detroit. See see see!”

Sharing the modest plush surrounding with Rachelle and Carl was suave cat, T.S. Eliot. Five years old now, T.S.'s large blue eyes were more at orbs and counted the molecules in everything that moved. He pretty much lived the life of a pampered rock star with a maroon diamond studded collar with silver Identification tag:

T. S. Eliot

5900 East Lake Drive

Lake Lansing, MI

Phone: 313-224-4454.

Email: [email protected]

T.S. was content with his surroundings and tolerated Carl. Carl, on the other hand, had never been happy living around “Moo U” (his slur for Michigan State) and, since he could remember, hated cats.

Pulling into the garage, Rachelle maneuvered to park as far to the right wall as possible to avoid, when opening her driver side door, nicking the spotless silver paint of Carl's BMW convertible. She had seen him freak out when anything got within a foot of his car, especially other car doors.

Briefcase in hand, she ascended the three steps and entered the kitchen. Stainless steel appointed, the room sparked with white tile flooring. An oak dining table sat in the center. The kitchen the bottom of an L, the vertical slightly larger than a tennis court, great room had two distinctive features—a two-story window view of Lake Lansing and, extending twenty feet to the cedar-beamed ceiling, a ten foot wide flagstone fireplace. The floor oak planking, the center of the room was covered by a large oriental rug. On the rug sat three white stuffed easy chairs, a glass coffee table, and a cushy white sofa. The wall of windows offered a post card view of the Lake’s shimmering water and distant shore. Sliding doors opened to a wraparound deck with steps down to a 15x30 swimming pool. A narrow brick path snaked down to the lake and a wooden dock to which, securely tied fore and aft by white nylon rope, bobbed Rachelle's twelve-foot Sunchaser sailboat, Percy Bysshe Shelley.

The great room log walls were decorated with water color paintings—sailboats, sea and landscapes—by Rachelle's father. One large red, black and white abstract oil, a gift to Carl from a lady-in-awe fan, hung closer to Carl’s made-to-specs block-glass cocktail bar. Three high-back stools faced the bar's onyx top. Detroit Lions glass ashtrays sat on the top. Flanking the mirrored back bar, on cedar log walls, a dozen framed photos of Carl in various football action shots–passing, running, posing–hung neatly in ordered rows. Also scattered around, on glass shelves, was an assortment of his gold and silver trophies—footballs, helmets, stadium replicas—awarded to Carl in his glory days. To one side of the trophies, stretched out on the wall, was Carl's Number 8 Lions football jersey. In the center of it all, his pride and joy, the Heisman Trophy rested in a Plexiglas case along with a recorder/playback unit and dozens of recordings—interviews, game highlights—from Carl’s football career. The recorder unit fed a twenty-one inch TV that hung above the back-bar.

To the left of the bar, a wrought iron staircase spiraled up to the second floor. At the bottom of the staircase, a door, painted Detroit Lions silver, led to a half-bath where, pasted on the walls, were newspaper clippings of Carl's college- and pro-football-playing heroics.

In the kitchen, T.S. rubbing her legs, Rachelle retrieved her journal from her belt pack, put it on the counter, and checked the answering machine.

“Rats.” Carl was right; she had forgotten to turn it on.

T.S. eyed her blandly.

She checked caller ID. Yep, Carl had tried to call, three times. “Rats.”

T.S. jumped on the counter, sat, and yawned widely.

She said, “Why didn't you answer the phone, Mister?” As if she might be an overnight guest, T.S. gave her a pious look.

“I live here too, you know.” She stroked his elegant head.

He looked at his blue T.S. Eliot engraved food bowl that sat on the floor.

“I know, I know.” She opened a can of his favorite Fancy Feast—ocean white fish with shrimp—and spooned the puree in the bowl.

He jumped down and, after a protest-pause, began to dine.

For herself, Rachelle poured a glass of white merlot, went to the great room and sat on the sofa. Looking over the latest issue of The Communication Journal, she sipped.

After reading the lead article, her wine finished, she figured a dip in the pool would be nice and went to the staircase and, T.S. behind her, spiraled up to the second floor. At the top she went to the three-foot wooden railing that overlooked, fifteen feet below, the great room.

Leaned back by her fear of heights, she looked beyond, out the two stories of windows, to the shimmering waters of Lake Lansing. She loved the view but this day, for some reason—melancholy, distant solitude—she turned and went to the bedroom suite. Wall-to-wall white carpet covered the floor of what Carl called his “love nest.” A double king bed, with blue and silver Detroit Lions' bedspread, dominated the room. At each side of the headboard, white shaded ceramic lamps sat on maple end tables. A white telephone sat on Carl's table. A window with white curtains offered a view of trees and could be opened for cool night breezes. A “Carl’s touch” TV/CD stereo combination faced the foot of the bed. A Casablanca fan hung from the center of the vaulted beam ceiling.

Off to one side, a sitting room had a mauve love-seat sofa and a small window with wood blinds beneath which sat a desk with a PC/printer setup.

A few steps from the sitting room, Carl's second favorite hangout after his bar, the bath featured a raised Jacuzzi tub and stall shower.

Rachelle and Carl shared a walk-in cedar closet dominated by Carl's suits, pants, sports jackets, and a shoe rack on which sat, shoe-horned and arranged in four stepped rows, his custom-made foot ware.

With T.S. watching every move, Rachelle stripped and selected a peach color one-piece swim suite. Her body easily a match for any twenty year old’s, she declined even at Carl's urging thong bikinis.

Her suit on, the presentation stunning, she grabbed a blue beach towel, went down stairs, outside, down the deck steps, and stuck her toe in the swimming pool.

T.S. sat on the deck watching her.

“Come on, chicken.” She dove in, swam two laps, and got out at the shallow end.

T.S. still on the deck, yawned.

“You should try it sometime.”

He yawned again.

“Yawn, brawn.” She said.

A warm evening, slight breeze, she toweled off and walked down the pier to Percy Bysshe Shelly.

T.S. raced down the steps and, in front of her, jumped on the bow. Staring at her, he seemed to be saying, “What are you waiting for, let's go.”

“Why not.”

Calculating a light wind out of the northwest, Rachelle untied the bow and stern lines, got on board, and hoisted the sail. Shimmering water, the sun setting in ripples of gold, the breeze in T.S.'s face, they reached the south end of the lake then turned and began running to the northwest and home.

After securing Percy Bysshe Shelley to the dock, the evening still warm, she decided to take another swim in the pool.

T.S. watched her glide through ten laps of the tepid water. Finished, sitting on the shallow end's underwater steps, she beckoned T.S.

He twitched his tail and went toward the steps that led up to the deck.

“You are such a snot,” Rachelle said, stepped from the pool, and began toweling herself. She noted the sun setting in streaks of reds and grays against a haunting purple sky. Unusually poignant, she thought.

Inside, T.S. following, she made a no

te in her writing journal of the sunset. Then, taking her journal with her, she climbed the spiral staircase, took a leisurely hot shower and, for pajamas, put on one of Carl's silk dress shirts. She opened the bedroom window. A pleasant breeze wafting the room, she lay down on the bed and snapped on a lamp.

T.S. Eliot curled up beside her, she checked the time: 8:30. She thought to herself, What was that start time, 6:00 West Coast, 9:00 here, have a half-hour before Carl's game begins.

She flipped the Casablanca fan on slow, fluffed two large pillows, lay back and, revisiting her father's favorite book W. Somerset Maugham's, Of Human Bondage, she read:

Cronshaw turned to Philip. “Have you ever been to the Cluny,the museum? There you will see Persian carpets of the most exquisite hue and of a pattern the beautiful intricacy of which delights and amazes the eyes. In them you will see the mystery and the sensual beauty of the East, the roses of Hafiz and the wine-cup of Omar; but presently you will see more. You were asking just now what was the meaning of life. Go and look at those Persian carpets, and one of these days the answer will come to you.”

She remembered, from a previous reading, the answer Philip had finally realized. She turned to a dog-eared page and read his thoughts:

The answer was obvious. Life had no meaning. On the earth, satellite of a star speeding through space, living things had arisen under the influence of conditions which were part of the planet's history; and as there had been a beginning of life upon it so, under the influence of other conditions, there would be an end: man, no more significant than other forms of life, had come not as the climax of creation but as a physical reaction to the environment.

She skimmed to an underlined passage:...then the sage gave him [an Eastern King] the history of man in a single line, it was this: he was born, he suffered, and he died. There was no meaning in life, and man by living served no end. It was immaterial whether he was born or not born….

Fake News

Fake News Truths of the Heart

Truths of the Heart The Journalist

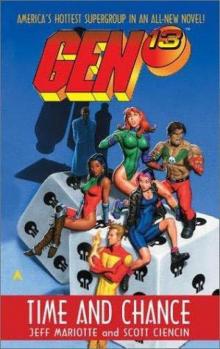

The Journalist Time and Chance

Time and Chance